‘Fly Me to the Moon’ - What Are the Artemis Accords and What Do They Mean for Russia-US Cooperation on the Moon?

Lisa Becker, UC Fellow (SciencesPo)

The moon - our planet’s only natural satellite - has always fascinated humanity. The Cold War pushed the boundaries as the Soviet Union and the United States engaged in a costly and dangerous space race. It culminated in the first man setting foot on the lunar surface in in 1969 in what was a “small step for man, one giant leap for mankind”. For nearly 50 years since, humans have not returned to the moon. This is about to change: both Russia and the United States have declared their ambitions to visit the orb as soon as this decade. Russia announced that it will proceed with 3D mapping the moon for the next crewed mission[1]. By the same token, with its Artemis Program the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) plans to send Americans to the moon by 2024[2]. The US-led program will unfold within the scope of the recently unveiled Artemis Accords, an agreement proposing an international framework for lunar activities.

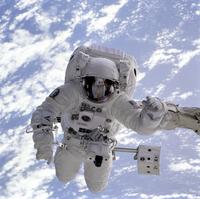

In space, US-Russia relations are torn between a commitment to cooperation and continuing competition. Despite the deterioration of the relationship on Earth, the Russian space agency Roscosmos and NASA continue to work hand in hand above our heads on the International Space Station, with American astronauts ferried aloft in Russian Soyuz vehicles. A new “lunar race” between Russia and the US would exacerbate existing tensions and risk escalation in an area in which this has previously not been an issue. Where do the Artemis Accords fit into this picture?

In 2015, the US passed the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act granting American companies property rights to resources they mine in outer space[3]. The Artemis Accords elevate these values to the international level: named after the twin sister of Apollo, the Goddess of the Moon, the agreement proposes a framework for international cooperation on the moon under the aegis of the US. It will enable private and public entities to pursue commercial activities on the moon that will be regulated by creating “safe zones” to deconflict lunar activities. Furthermore, it calls for mutual commitment to emergency assistance, interoperability, debris mitigation, the registration of space objects and sharing of scientific data among the partners[4].

The moon is considered a global common. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty (OST) established that “celestial bodies and the moon are not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means”[5]. The OST is the only international treaty that applies explicitly to the moon and counts 109 parties, including Russia and the United States, as well as China[6]. In an attempt to codify laws for the use of celestial resources, a series of UN-sponsored conferences led to the draft of the 1979 Moon Treaty, the Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies[7], but the main spacefaring nations withheld their signatures and subsequent efforts at negotiation did not bear fruit.

Access to space has increased with the proliferation of space technology, which is becoming smaller and cheaper to launch, enabling more players to engage in spatial activity. This has opened up commercial opportunities. The moon has become a strategic asset and holds promises for the future: mining abundant resources like rare metals and helium-3, is a lucrative business potentially worth billions of dollars[8]. In a second step, the moon will be transformed into a pitstop for further space explorations. Russia and the US, along with their ISS partners, participate in the Lunar Orbital-Platform Gateway project that will see the creation of a cislunar outpost orbiting the moon[9].

Prospects for new joint opportunities on the moon come at a suitable time: the future of US-Russian space cooperation is uncertain as we close with the horizon of existing projects. The ISS, a flagship project, will be deorbited in 2024; until then, Russia has reluctantly agreed to remain on board[10]. What happens beyond that is written in the stars. As the US is slowly but steadily acquiring autonomy in transportation, an important pillar of long-standing cooperation with Russia in human spaceflight ever since the end of the Shuttle program in 2011 will be terminated - a rupture that will not go unnoticed in the current international environment. This is why joint undertakings on the moon like the Lunar Gateway promise some continuation of the older cooperation. “Ambitious projects related to exploration of the Moon could become a serious factor in cooperation of the two countries in difficult times” Sergey Saveliev, Roscosmos’ Deputy Director General for International Cooperation, affirmed[11]. Yet, American Vice President Mike Pence did not mention Russia among the partners in his remarks at the National Space Council meeting on May 19th, 2020[12]. Dmitry Rogozin, Head of Roscosmos, made it clear that Russia will not content itself as a junior partner in any US-led project[13].

Cooperation on the exploration of the moon is off to a rocky start. The following factors will determine the future of the US-Russian partnership on lunar activities and the success of the Artemis Accords.

First of all, the “lunar gold rush” highlights fundamentally different approaches to the moon and space altogether: as per executive order, the Trump administration affirms that the US does not view the moon as a global common[14], while Russia considers the celestial body as part of the heritage of all mankind. Therefore, it is not surprising that the unveiling of the Artemis Accords has not been well-met in Moscow. After the news was leaked a week before the official publication on May 15th[15], Rogozin tweeted that “the principle of invasion remains the same, whether it is on the moon or Iraq”, calling out the US for forming a “coalition of consenting”[16]. A series of bilateral agreements allows the United States to collaborate with “like-minded” spacefaring nations; Russia was allegedly excluded as an early partner due to its engagement in proximity operations[17]. Despite the miscommunication leading Moscow to believe that it was not welcome, NASA officials have since clarified that all ISS partners are invited to join[18]. Still, the Kremlin’s spokesperson Dmitry Peskov insisted on a thorough analysis to check whether the agreement is compatible with the OST, especially with regard to what he called the “privatization attempt” and claims of sovereignty, referring to the “safe zones”[19]. Russia is conspicuous in its insistence that it will not tolerate unilateral advances of the US-led initiatives that forgo existing principles, and wants to set the agenda within a partnership based on an equal footing.

Next, Russia and the United States are not alone in their aspirations to conquer the moon. A rising space actor, China has announced ambitious programs for the exploration and subsequent presence on the moon as well[20]. The Artemis Accords, however, could exclude Chinese participation under congressional restrictions[21]. There has been a rapprochement between Russia and China who show aspirations of wishing to shape space together: they submitted a draft treaty on the “Prevention of Placement of Weapons in Outer Space” at the UN[22], signed a memorandum for moon exploration[23], and negotiated an agreement on joint lunar research[24]. In light of the exclusion of China due to American reservations, on the one hand, and the strained US-Russia relations on Earth on the other, an intensification of Sino-Russian cooperation in space will draw the US and Russia apart.

Not only have the number of spacefaring nations increased, but companies play an increasingly central role too, especially when it comes to the moon. The Artemis Accords apply to international space agencies; any attempt to regulate moon activity would have to explicitly take the private sector into account.

Lastly, US-Russia relations have seen better times and this shows in space too. NASA Administrator Jim Brandenstine said that space is the “best opportunity to dialogue when everything else falls apart”[25]. And despite the pandemic, President Putin believes that “even now, when the world is confronted with challenges, space activities will continue, including our cooperation with foreign partners”[26]. Space, however, is not immune to politics: meetings between Roscosmos and NASA have been postponed or cancelled because Rogozin’s visa application was denied and the US Congress blocked travels to Russia[27]. The relationship between Bridenstine and Rogozin is an epitome of the volatile relations that range from invites to alma maters all the way to heated exchanges on social media[28]. Additionally, increasingly hostile military postures[29] and manoeuvres[30] further jeopardize civilian cooperation that is being progressively overshadowed by security considerations in orbit. To believe that space is a sanctuary does not do justice to the risk of even accidental escalation. Ultimately, it will depend on the administrations and whether they believe that the benefit of cooperation outweighs the harm of terminating it.

More than 50 years after the first human stepped onto the lunar surface, the quest for the moon has gone into an all new round that sees increasing competition among a larger number of players with ambitious goals. The Artemis Accords promise to become building blocks for a framework for lunar activities, but fail to address the issue in a way that would foster international cooperation. It is a series of exclusive bilateral agreements initiated by the US administration; meanwhile, the actual challenge of creating a global governance framework remains. Now more than ever, there is the need to engage in a comprehensive dialogue on the regulation of space in general and of the moon in particular to avoid setting off a lunar race with a “first come, first serves” ethos. It will take a joint effort of Russia and the United States together with its allies to bring China and other space actors to the table and set rules to enable the responsible and sustainable exploration of outer space.[31]

[12] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-vice-president-pence-7th-meeting-national-space-council/

[14] https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/executive-order-encouraging-international-support-recovery-use-space-resources/

[20] https://www.scmp.com/news/china/policies-politics/article/2093811/china-plans-ambitious-space-mission-hunt-and-capture

[22] Draft of the Treaty on the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space, the Threat or Use of Force against Outer Space Objects; available via: https://reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Disarmament-fora/cd/2014/documents/PPWT2014.pdf

[28] https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2019/01/nasa-roscosmos-russia-bridenstine-rogozin/579973/

[29] In the revised Russian military doctrine from 2014, the loss of control in space as a major military threat and puts the supremacy in space as a decisive factor of achieving military goals. The 2018 US National Defense strategy proclaims space as a “warfighting domain” and consolidated this change with the establishment of the Space Force as a separate sixth military branch. Similarly, at the meeting in December 2019, the NATO allies declared space as its fifth operational domain. (Russian Military Doctrine 2014, §21м; US National Defense Strategy 2018; NATO London Summit Meeting 2019)