The UC Interview Series: Prof. Roy Allison

by Muling He

Muling He: Muling He is an M.A. candidate at Harvard University's Russia, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia program. He is from China and graduated from Carnegie Mellon University with a degree in philosophy and Russian studies. In his undergraduate studies, he completed a thesis on media in the Cold War and the Sino-Soviet Split. Muling is currently researching the political and spatial changes in Central Asian mahallas during the Soviet period. He is also broadly interested in Eurasian history, ethnography, and literature. He is also affiliated with the Columbia University law school.

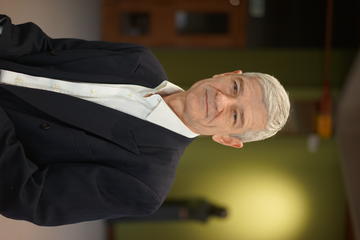

Roy Allison: Professor Roy Allison is a University Consortium Principal, Professor of Russian and Eurasian International Relations, and Director of the Russian and Eurasian Studies Centre at St. Antony's College, University of Oxford. His research focuses on the international relations, foreign and security policies of Russia, Ukraine, and the countries of Central Asia and the South Caucasus. His recent publications focus on Russia and its approach to international rules, law, and norms. These include his book on Russia, the West and International Intervention (Oxford University Press, 2013) and articles in International Affairs, 'Russia and the Post-2014 International Legal Order: Revisionism and Realpolitik' (2017), ‘Ukraine, Russia and State Survival through Neutrality’ (2022).

Past experiences: on going to the USSR by boat, on the collapse of the USSR, and on building new academic collaborations in Russia and across the post-Soviet space.

Muling: Thank you Professor Allison for taking time for the UC Interview Series. Let us start at the very beginning of your career. How and why did you enter the field and what was it about Russia and the East European region that fascinated you?

Roy Allison: For that, we have to go back to the Cold War period. I suppose my original interest in Russia was the result of two quite separate matters. One is just Russian literature. The culture was something, as with many, that introduced me to the country. But also, I used to travel when I was young to Finland because my mother was from there. There was always the intriguing question about what existed on the other side of the border. We traveled quite a few times also on the boats run by a Soviet shipping company that operated a route from London all the way to Helsinki. So, I was exposed to Cyrillic letters and got Soviet food there.

With this in the background, I shaped my first degree into something of a Russian studies degree, studying both the history and the politics. One of my professors also suggested to me that the relationship between the Soviet Union and Finland was a big puzzle, so I worked on it and applied to Oxford to study this relationship. I was fortunate in completing this project and also getting a postdoctoral research fellowship soon after. I suppose I was on a certain course by that stage.

Muling: Had you travelled to the Soviet Union by this point?

Roy Allison: Yes. Even before I really knew what it was. I think I was there first when I was seven years old. I was in St. Petersburg and only there, where this Soviet boat stopped. We stayed on the boat but did some sightseeing from it. Therefore, I have some distant memories of differences and also of some interesting similarities – the architecture was not so different to that in Helsinki, for example.

Muling: I guess that after you entered the stage of research, your impressions became probably very different?

Roy Allison: Of course. By that stage, I had an understanding of the political system with all its problems and challenges, as well as the nature of Soviet social organisation and foreign policy, which I was studying. So, I saw this much more as a problematic state with all the dimensions of that. But it was still intriguing, and I still felt the need to try and understand the processes and direction of development in it. And I was solving that puzzle too, about how such a large power could allow a small state on its border to coexist and be politically independent. I did not actually go back for study purposes to the Soviet Union until 1985. And that was for my postdoctoral fellowship. I had an attachment to the Department of International Law in the Law Faculty of Moscow State University in 1985 and I managed to get there on a British Council exchange scholarship.

Muling: Wow! You were there in a very turbulent time for the Soviet Union. How did you view the dynamics within the USSR during this time as a political science student?

Roy Allison: Well, initially in 1985, it did not seem to change much at all. In fact, various forms of repression intensified at the beginning of the Gorbachev period, including the Afghanistan campaign. I was only in Moscow for a few months. So, it was not an easy period to be there. It was very difficult to have proper conversations with Soviet citizens. It was quite like the experience of many before, rather isolated. But I did make some academic connections, some were quite reformist thinkers, even though they could not express their opinions properly at the time. What was unusual was that when I came simply as a postgraduate student, I was invited soon afterwards for drinks with the British ambassador on the veranda of the embassy. It was the result of the fact that there were very few British citizens apart from journalists in Moscow at the time. For foreign scholars, there were a lot of bureaucratic problems and not that many came, so my visit made me visible even on an ambassadorial level.

Muling: I see. Would you say that these reform-minded people you met were representative of the people you encountered during this period in the Soviet Union?

Roy Allison: Well, I think that there were more of them in the universities, especially in stronger research universities. They understood the need for change, but the opportunity for expression was still very limited. I attended some of the faculty meetings in the university just to listen in on these discussions and they were quite formal. You would not think of them as the source of original ideas.

These people began to emerge in public from about 1986 and 1987. When I started traveling back to Moscow a little bit later, I began to meet some of those who contributed to the so-called “new thinking” in foreign policy. They came from different professions. Gorbachev gathered around him a set of people from a whole variety of professions, to begin developing ideas that he subsequently took forward.

Muling: This is very interesting! What sort of professions were there?

Roy Allison: Oh, there were all kinds. For example, Aleksandr Bovin was a very high-profile journalist. There were nuclear physicists, who helped Gorbachev understand the real threat of nuclear war and nuclear winter. There were people from the social part of society.

Gorbachev stayed in contact with many of these people. It was a circle that continued even after he left power, into the 1990s. I know this because I attended a two-day seminar at the Gorbachev Institute, where he assembled some of his old friends and colleagues. They were still obviously in touch with each other. He himself was still interested, still driven by ideas and excited by thinking about change even if he was no longer in power.

Muling: Let us fast forward a bit. You became the head of the Russian and CIS Programme at Chatham House in 1993. This was the time of another transformation in Russia. I wonder, what were some of your expectations of what Russia would become at this time, and what was the atmosphere like at that time?

Roy Allison: I spent a couple of months in Moscow, including August, in 1991. I had a sense of the transformation occurring in Russia at that time already. I actually changed my research agenda quite radically. I was working on a book called “Radical Reform in Soviet Defence Policy,” but the reform was so radical that the Soviet Union collapsed. Much of the book was no longer very relevant, and I think the publishers never recovered the cost for publishing it. But I went on to study the new republican armies that were developing in Soviet republics even before the end of the Soviet Union.

I could also see the diversity in the national agendas of different post-Soviet states. This excited me because there no longer was a need to focus solely on Moscow and Russia. When I took on the job at Chatham House, we started developing new contacts, received guests from different republics, and organised seminars for bilateral exchanges with institutes in all these new post-Soviet states. I traveled a lot for those purposes. I think that there was a sense of real momentum and opportunity.

Russia, in 1993, under President Yeltsin, was already becoming a little more guarded in its approach to Western states. There was also a resurgence of more nationalist opinions in the state. I never felt that there was any automatic direction or development towards full-fledged democracy and civil liberties. Russian society was hugely diverse, and the “new thinking” under Gorbachev did not sink its roots very deeply in the Russian elite or the political body. We encountered a lot of different politicians. We met many post-Soviet leaders, opposition figures from different backgrounds, as well as those who were within the government. Sometimes they came as part of the Foreign Office Overseas Visitors Program. We had one-to-one or small group meetings quite frequently. These encounters also made me feel cautious about simplistic thinking about the course of Russian development.

In summary, I think there was a sense of real opportunity and a lot of commonality with Western states, but I also felt the potential for change in directions which were less desirable.

Muling: Would you say that during this period, for the intellectuals you worked with, there was also this reserved, more constrained attitude towards the West?

Roy Allison: It varied very much. There were those who really believed that Russia was on a unidirectional course. In some ways, the whole concept of the transition from one system to another was underpinned by that belief. I always thought that was rather deterministic. It seemed to me that there were a number of different directions possible in Russia and that politics had a lot to do with it. In the early 1990s, some felt that Russia's development was driven by the huge economic transformation that was underway, but at the same time, a lot of people suffered through the socio-economic aspects of that transition. The political effects of this became apparent only later.

I think in the West, there were those who felt that one way or another Russia would be pulled or would pull itself more in a “Western” direction. Others, me included, felt that it was more nuanced and that one could not simply rely upon President Yeltsin to be able to somehow pull the society along in one direction.

Russia had not had a democratic tradition, and its experience of democratic political processes was limited. This meant that the values we hoped Russia would continue with were not deeply felt in the society.

Muling: Along this line, how do you think collaboration between Russian intellectuals and Western intellectuals developed over time, up to today?

Roy Allison: A lot of opportunities arose in the late 1980s. New exchange programs between universities, between different aspects of civil society, scientific organisations, and businesses became possible. There was an increasing understanding that Russia's development would be influenced by this age-old search for what Russian identity really is, and whether Russia would develop a more civic identity or something more ethno-nationalist. You certainly saw evidence of this more nationalist perspective developing at the expense of other Russian Federation units. This was also true for other CIS states.

Yeltsin tried to sustain a relatively free press. It was an achievement, but it also meant a lot of fluidity and uncertainty in politics. The archives were also open for historical research; however, it was necessary to work through Russian institutes and intermediaries to be able to get things done. It meant you had to have access to officials, in order to have access to events and archives and so on.

In 2001, with 9/11, a different, security basis for cooperation emerged. But that did not really last very long. It did not have a very deep imprint on the Russian official world. Then further into the 2000s Russia began to define itself, not just with European values, but also something in addition to that: European, but with certain Russian characteristics. It became increasingly Eurasian, and then moved into more nationalistic directions.

Current Issues: on Finland, on separatism, and on changing international order.

Muling: Have the events resulting from these changes, such as the Russian military actions in Georgia, in Ukraine, caused damage in the cooperation between scholars from the West and Russia?

Roy Allison: Yes, but it is more about the climate in my opinion. At the university level, expert to expert level, they were less influenced by external developments, particularly the 2008 Russian-Georgian war, which had a fairly limited influence on thinking. It was, after all, brought to an end with mediation from the European Union largely accepting a Russian ceasefire blueprint.

On the Russian side, the constraints were more with Russia's growing belief that somehow the Western states, European states, and the European Union were supporting the so-called “colour revolutions.” I think 2005 was an important turning point in Russian thinking. People interpreted the Orange Revolution as a competition with the West and Western values. Russia feared the Rose Revolution and the Orange Revolution. There was also the 2011 Arab Spring, which was associated with these “colour revolutions” as being somehow driven by Western or external agencies.

This belief and demonstrations in Moscow against fraudulent elections in 2012, led to more controls over civil society and increasing suspicion to Western experts and projects. By this stage, we could not develop projects like we did in the early 2000s anymore, even with Russian partners. Regulations also restricted Russian institutions to accept funding from outside, for example.

Muling: That is very relatable. In China, the government genuinely believes that Western scholars and governments are trying to stir up “colour revolutions.” Whether people in the universities believed in it or not, there is pressure to act according to this perception. Do you think this largely official perception reflects a genuine belief among scholars in Russia at this time?

Roy Allison: I doubt that because there was not really the evidence to back it up. Those who were working with Western scholars would know well the nature of their work and the kind of seriousness with which they took their studies, as well as the genuine interest in and hope for a positive development in Russia. In the main research universities, I do not think that there was the view that Western experts were working on behalf of their states.

There was much less tolerance for NGOs working to strengthen civil society in its various forms or promoting democratisation or so on. But if you were working on other kinds of projects, it was difficult to credibly claim that it was part of some wider Western agenda at the expense of the Russian system. Scholars understood that and there was a lot of joint work underway.

Muling: You have worked on Finland from very early on in your career. Today, at the advent of the Ukraine War, Finland along with Sweden have again become the focus of attention. What do you make of this strategic shift: these two countries potentially joining NATO?

Roy Allison: The two countries are similar and somewhat different. For Sweden, neutrality has been more a matter of identity for hundreds of years. To change and move away from that is really quite a wrench. For Finland, neutrality was more a pragmatic decision. So the society and Finnish elites have decided that it is not sufficient anymore. In fact, Finland has not been talking in terms of neutrality for many years. It has been more about military non-alignment.

Russia always had a concern about the security of the Kola Peninsula because of the nuclear assets it had there. But apart from that, Finland was a little bit of a sideshow. The USSR had the minimal objective of ensuring there was no potential for any attack against it through Finland, and this was covered by the Finno-Soviet Treaty of 1948. There were not even serious attempts to turn Finland into a “people's democracy” as there were in Central Europe.

Finland developed its understanding of neutrality through some peacekeeping activities and some mediation diplomacy and so forth. This was possible in a period when it did not seem very likely that Moscow would attack a small neighbour country. Despite this, Finland and Sweden were very cautious. They kept and developed their territorial defence systems through the Cold War and in the case of Finland also post-Cold War. The military establishment and security were very much focused on maintaining that capability, intended against the scenario of a large-scale, conventional offensive from the East.

Therefore, Finland has not had to really change its defence configuration or planning to any significant degree. But what has changed is the perception of the likelihood of a serious confrontation with Russia. The recent language of nuclear coercion by Russia is also unprecedented. Since the end of the Second World War, we have not had that kind of language coming out in that way and fairly consistently.

So new concerns have arisen: how far can you rely on conventional deterrence against nuclear threats? Is there a possibility of an economic blockade in a crisis, because Finland relies on trade through the Baltic Sea so much? Therefore, joining NATO is now seen as really a necessary step. Finland had always kept this option open and made clear that this was a security option available if circumstances required. Sweden came around to a similar view and both countries are very determined to take this step. The timing now is also rather crucial because Russia is hardly in a position to take any effective countermeasures because of the war in Ukraine.

Finland, in entering NATO, has made clear that it is not going to be a country that is a liability for NATO military capabilities, rather it is a net contributor. It can look after its own defence in most expected cases. But it does need a bit more reassurance particularly because of this issue of nuclear coercion.

It demonstrates nicely the question how much additional benefit is gained through the Article Five of the NATO treaty. Article Five is not some kind of hallowed principle that should be blindly relied on. Countries do also need to look after their own defence. This also includes Ukraine. So whatever future scenarios we can think about for Ukraine, I think it will be essential that it develops highly capable, well-equipped, up to date defence forces, supported by a large-scale territorial defence system. If it can do that effectively and also have some guarantees of additional Western support, the whole idea of the Article Five defence guarantee may fall away as being really less important.

Muling: When observing the current situation do you think Russia is trying to create a legal framework to justify its actions in Ukraine? And do you think this will have a broader impact on the stability and universality of the international legal order?

Roy Allison: Russia's efforts now are very transparent and very unpersuasive. In the past, there was a more conscious effort to do this, although many of the justifications were inconsistent with each other. With the 2008 Russian-Georgian War and the annexation of Crimea in 2014, there was this very shallow effort to provide a cover for the formal recognition of the breakaway republics, which then Russia regarded as states. These states, in turn, could call on Russian assistance for “collective self-defence.” In February 2022 in the case of the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic Russia signed bilateral defence agreements with these entities, and used this to claim that in response to a supposed Ukrainian attack against these “republics” it could assist militarily as a matter of collective self-defence. This really is completely unconvincing, and I think that even countries that in other respects have been sympathetic towards Russia, would not be convinced by this as a legal argument.

I think that the purposes of such legal rhetoric now are more for Russia's domestic audience and to some extent, I still think they are intended to cause some confusion about the nature of Russian military aggression for countries which would really prefer not to commit themselves to open condemnation of Moscow. We see this in the abstaining votes in the United Nations General Assembly.

What is happening now is such an open violation of the fundamental prohibition against territorial aggrandisement. Territorial war is not just an illegal use of force. There have been illegal uses of force at various times and other great powers occasionally do this too. But this is of a completely different order. It is not only against the so-called liberal or western rule-based international order. It is, I believe, a fundamental challenge to the universally understood legal principles underpinning the United Nations Charter. If it is not condemned, then it can weaken the constraining effect of international law around these most fundamental UN Charter principles.

Many countries have concerns about possible violations by stronger neighbouring states or predatory states. Weaker countries rely more upon the constraints in international law. For this reason, I think that it is not helpful for them to look away on the question of separatism, which Russia has again been empowering. Most countries will agree that sovereign states are the basic units of the international system and that states cannot just create other states out of their neighbours. This is true for China, which has its concerns in Xinjiang, Taiwan, and Tibet. India with Kashmir, Iran with the Azeri areas, Turkey with the Kurdish areas, and so on. It goes on and on. Many CIS countries have equal concerns. Russia has already been encouraging separatism, but now it goes a step further, carving out territory and trying to attach it to itself. This is something we have not seen in the post-World War II period.

Muling: But what makes the difference between what Russia had done in Georgia in 2008, when two territories were carved out and now are effectively separate from the Georgian state?

Roy Allison: It goes one stage further because Russia did not recognise these territories as being part of the Russian Federation. Some of the leaders in South Ossetia had called for unification with their northern counterpart, North Ossetia which is part of the Russian Federation, but this did not happen. What is happening now is much more straightforward. Now one of the lessons is that there should have been a much stronger international reaction to Russian actions in both 2008 and 2014, because allowing these grave territorial violations of Russia’s neighbour states to pass over made it easier for Russia to contemplate doing something more extreme in Ukraine, as has happened.

Muling: That is a great point. The reaction now in Kazakhstan has been particularly attention-drawing. This leads us to consider the change of the role of Central Asian countries in this. The region has traditionally been perceived as one that supports Russia. Some would even say it is Russia’s “backyard.” Now we see a rather changing landscape. What do you make of this?

Roy Allison: Yes, I think the Russian-Kazakh relationship is one of the key axes that Russia has sustained since the end of the Soviet Union. It has been a special relationship for both sides. But for Kazakhstan, all its talk about Eurasianism and entering Eurasian organisations has been a way, I think, to try to ensure that its ethnic Russian population does not feel cut off. For the same reason, Kazakhstan has not promoted the identity of an ethnic Kazakh state, but a civic identity which incorporates all the peoples within the state.

However, there has been a continuing concern about the northern and eastern areas of Kazakhstan, which are mostly populated by ethnic Russians. This issue was more or less closed between Russia and Kazakhstan in the late Yeltsin period. But now, there are occasionally politicians who make nationalistic comments about it. What has happened with Ukraine and also the way in which it has been justified by Moscow, on grounds of so-called historic justice, could apply to areas of Kazakhstan as well. So, I think there is a sense that the war really is a challenge to Kazakh sovereignty as well.

President Tokayev has, in response, made clear that he is for a sovereign Kazakhstan, even if it means distancing himself from the kind of rhetoric that Russia has been using. He also has to continue to be careful about domestic socio-political cohesion in Kazakhstan.

The very serious unrest in January 2022 in Kazakhstan had more to do, I believe, with socio-economic issues and corruption, rather than issues of ethnicity. But it made the state more alert. Kazakhstan also knows that its economy is likely to suffer if it is too closely bound up with Russia. So there has to be a balancing act for the country.

Muling: Russia has been gathering support from non-Western countries such as China, Iran, and Turkey. Do you see these countries emerging as a united force capable of shifting the international rules in some way against Western interests?

Roy Allison: Well, I think these countries have a somewhat different set of priorities to Western counterparts. Their policies are not oriented towards those of Western nations. They make their own judgments about political systems and domestic political arrangements. In some cases, in India and South Africa for example, there is still quite a strong legacy of anticolonial feeling. Such views persist over decades.

More recently, Putin has also pivoted in his rhetoric to a strong focus on anti-colonialism. Russia seeks to present itself as a new anti-colonial champion, which is in some ways quite a strange role projection if you consider the political composition of the Russian Federation as a state as well as its actions. But this strategy has seemed to gain some attention among elites in different non-Western countries. Russia hopes this way to become a leader in not just a multipolar but also perhaps “multi-normative” order.

India is taking quite an independent position, too. But on questions of democracy you find a lot more overlap with the Western understanding of appropriate behavior.

China also looks after its own interests. It does have some common language with Russia, but it does not need to rely on it. China is developing its own understanding and over time, it would wish to shape the norms governing the international system and to influence the definition of international principles more in favor of its own preferences. Rather than directly challenging the current international order, this expresses more a desire to transform it gradually and to gain more acceptance from other states. In this sense, China does not want to disrupt the whole system. Its approach is more evolutionary.

Regarding the Ukraine War, China also understands the risks of accepting or not condemning separatism because it is a basic principle for the state. Thus, it will be watching the situation very carefully. It is also learning the extent to which the international community responds to Russia's effort to annex territories. One lesson that might already be emerging is the strength of resistance by the Western community. It is much greater and more coordinated than perhaps China expected, certainly than Russia expected.

Messages to the young generation.

Muling: You were a student at Oxford, and you have returned here to work as a professor. What made you come back and how did your perspective change? Did your student experiences inspire your efforts to develop this institution you are working in?

Roy Allison: I never expected that I would have the opportunity to return in the way that I did. It is a great honour to be back as a fellow of the college. I was a postdoctoral student for a number of years, and I did keep quite close relations with the Russian and Eurasian Studies Center in St. Antony’s. When the job opening came up, I saw it by accident and it just fitted my interests so well, so I applied. It is useful to have that background in the college because I have a kind of institutional memory of how it worked and how it was. I think my student experiences have helped me connect with the concerns and attitudes of students. It helped me understand the difficulties of sustained doctoral research over many years.

I have seen how the priorities of the university have changed; the nature of research as an activity has also changed. We now have all kinds of sources and materials available. Now many things are digitalised too. We have huge additional resources and opportunities. For example, now we hear the talk about a new Cold War as an existential challenge to studies. But it was possible still to do significant research during the actual Cold War. There was a huge industry of research on the Soviet Union, and many more books being published then in our field, on our region, than there are now. There is also the concern that countries in our region have become inaccessible and that is a terrible thing. With Russia there is great uncertainty. But I believe that, over time, some countries become inaccessible, then they become accessible again later. Currently some are becoming more accessible, such as Central Asian countries.

Muling: That is a great point. For example, many of my colleagues have conducted work this year in Kazakhstan and I just came back from Uzbekistan. These countries have been more willing to open up.

To conclude, we would like to ask: What other messages do you have for students of this current and upcoming generation? Would you recommend that we study this region in such a tumultuous time and why?

Roy Allison: I think so. It is good to have a comparative approach. It allows you flexibility in where you may have to focus your studies or if you wish to do field work, where you can actually conduct it. But more importantly, it also allows a broader scope. You will also be able to connect with students and researchers in different fields. So, it is very helpful to have an understanding of what your primary discipline is. Other scholars might have less area studies knowledge, but they likely have the disciplinary expertise.

Also, as I said, I think opportunities arise and it is difficult to know when a knowledge base or skill set will be important. When transformation occurs in Russia, it can become an easier place to do research. When it becomes more accessible, we should have people trained to do research there. For the time being, I believe we should focus on developing critical thinking, which is core to scholarship. We should also continue to engage with people within Russia on that basis.

Muling: Thank you so much for your time today, Professor Allison!

Roy Allison: Thank you. My pleasure.