The UC Interview Series: Prof. Archie Brown

by Natalie Hall

Interviewer: Natalie Hall

Natalie Hall is an M.A. candidate in Regional Studies: Russia, Eurasia, and Eastern Europe at the Harriman Institute. She earned her BA in International Affairs from the Elliott School of International Affairs at the George Washington University, where she concentrated on Security Policy, with minors in Slavic Studies and History. She studied abroad at KazGU in Almaty, Kazakhstan for six months focusing on Russian language and Central Asian culture and history. Prior to starting her studies at the Harriman Institute, she worked at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace on the Russia and Eurasia Program, and at Eurasia Foundation. At the Harriman Institute she focuses on Eurasian security matters.

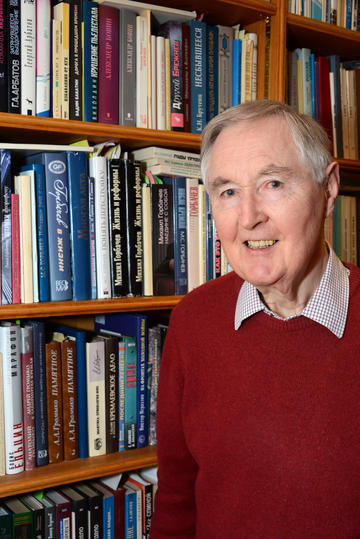

Interviewee: Archie Brown

Archie Brown is an Emeritus Professor of Politics at Oxford University. Previously, he lectured at Glasgow University (1964-71), during which time he spent an academic year as a British Council exchange scholar at MGU (Moscow State University). He became a Fellow of St Antony’s College, Oxford, in 1971. He has held visiting professorships at Yale, the University of Connecticut, Columbia University, and the University of Texas at Austin, and was Distinguished Visiting Fellow at the Kellogg Institute for International Studies at the University of Notre Dame. Professor Brown was elected a Fellow of the British Academy in 1991 and a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2003. He has written extensively on Comparative Politics, particularly on leadership, political culture, and Communist politics (especially Soviet). His most recent book is The Human Factor: Gorbachev, Reagan, and Thatcher, and the End of the Cold War (2020). Others include The Myth of the Strong Leader: Political Leadership in the Modern Age (2014), The Rise and Fall of Communism (2009) and Seven Years that Changed the World: Perestroika in Perspective (2007).

Past experience: On Prague Spring, Mikhail Gorbachev and perestroika, and advising leaders.

Natalie: We'll start with your past experience; why and how did you decide to enter the field of Russian and Eurasian Studies? Which at the time was Soviet Studies of course.

Archie Brown: In my case it was accidental. Some people got into Russian, or then Soviet, Studies because they were attracted to Communism; I certainly wasn't. Or they had a fascination with Russia; I didn't at that time. Rather, when I was in my final year as an undergraduate, at the London School of Economics, I wanted to write an essay on Soviet politics to be better able to answer a Soviet question in the Comparative Government paper. My tutor was a specialist on British politics, and he said he wasn't qualified to assess it, so he would “give it to Mr Schapiro”. Leonard Schapiro was the leading British specialist on Soviet politics and the author of a major book called The Communist Party of the Soviet Union. He called me in to see him, and he liked my essay. So much so that he encouraged me to apply for a graduate studentship at the LSE funded by the Ford Foundation. I was pleased to get one of the three advertised studentships, for the selection was made by an impressive committee. It was chaired by Michael Oakeshott, a distinguished political philosopher, and the committee included not only Schapiro but also Alec Nove, one of the world’s leading specialists on the Soviet economy. It would never have entered my mind to study Russia or the Soviet Union but for my tutor giving the essay to Schapiro. It was quite a happy chance, because I've got no regrets about the path my ensuing career took.

Natalie: I was wondering what your recollections of the Soviet Union were from this kind of early period of your life, around and after Stalin's death and if you sort of had a sense for what the Soviet Union was like in the world at that time.

Archie Brown: Well, I would say that my image of the Soviet Union then was of a totalitarian state. The general view in the West was that all Communist states were totalitarian. Even as an early teenager – this was in the early 1950s – I read George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm, so I didn't have any illusions about Stalin's Soviet Union as it was then. By the time I was studying at the London School of Economics it was the Khrushchev era. As an undergraduate I attended the lectures and, as a graduate student, the seminars of Leonard Schapiro who was a fine scholar. However, he viewed all Communist states as totalitarian by definition and that reinforced my views at the time. This, then, was my starting point. A visit to Czechoslovakia, before I had ever set foot in the Soviet Union, made me reassess that judgement. And when I subsequently went many times to the Soviet Union, I found that there was far more diversity of opinion than I had been led to expect, even within the ranks of the Communist Party.

Natalie: You just mentioned your visit to the Czech Republic, or Czechoslovakia, as it was known then. I was really interested to hear about how your perceptions changed about the Eastern Bloc and your perceptions of governance, culture, and as you noted just now, diversity. That's a really interesting question to me - tell me more about that.

Archie Brown: It was a very important visit for me. By that time I was a Lecturer in Politics at Glasgow University. Alec Nove had moved from the LSE to Glasgow University, and he asked me one day if I'd like to be a member of a group of four people going on an exchange visit to Czechoslovakia. I said, "yes, I've never been to a Communist state before."

We went in late March-early April 1965. The other three people were interested in the economy and economic reform discussions, while I was more interested in the political system. And even though I came with this totalitarian concept in my head, at least I had a sufficiently open mind to want to know whether there might be opinion groupings and interest groups within the system, and whether there was any discussion of possible political reform. It turned out to be a very good time to go there because, unnoticed in the West, there was a movement for reform within the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia which really got going in 1963 and culminated in the Prague Spring of 1968. Some of the people I met in 1965 played a prominent role in the Prague Spring. The most important of them was Zdenĕk Mlynář, who in 1968 became a Secretary of the Central Committee, briefly a Politburo member, and he was the main author of the Action Programme of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia in ‘68. I met him in his home and had a long discussion with him. From him and from other party intellectuals I met on that visit, I learned that there was an upsurge of reformist thinking within the Communist Party.

When I went back to Glasgow and spoke with the Lecturer in Czech there, Lumir Soukup, who had been private secretary to Jan Masaryk in the post-war coalition Czechoslovak government, he was utterly sceptical that Czech Communists, whom he had encountered before they seized full power in 1948, could come up with anything good. But in 1968 he recognized that very important change was taking place. He himself was interviewed on Czech TV in that year.

That first of my visits to Czechoslovakia was valuable for me. I realized that in a very different way from Poland – where change in the Communist era typically came from below, through massive strikes and a series of popular movements culminating in Solidarity in 1980-81 – you could have a serious movement for change from within the ruling party. And the Prague Spring showed that intraparty change could be one way of moving even to systemic change. That opened, in principle at least, the possibility in my mind that this could happen in the USSR.

Natalie: That's really an interesting point that you raise because I think one of things I have often noticed in the field is that the collapse of the Soviet Union and all of the reforms that preceded seemed like a shock to some Sovietologists, but it sounds like you sort of had an awareness that that might even be a possibility long before it actually happened.

Archie Brown: I certainly wouldn’t claim to have foreseen all that was going to happen. I don't think anyone could or did, and that includes Mikhail Gorbachev. However, I thought that far-reaching change was possible in principle, and that it depended on a reform-minded leader becoming General Secretary of the Communist Party. When I first went to the Soviet Union in the mid-1960s, I found people with a wide range of critical views, but almost all of my friends at that time were not party members. They kept a distance from the Communist Party; some of them were completely apolitical. It was only from the mid-1970s and especially from 1979 onwards that I had conversations with members of the party intelligentsia in Moscow who were willing to express critical views in private conversation with me. It was clear that there were within the party people dissatisfied with the system, or at least the way it worked, but the question still was: could anyone who was sympathetic to reform become General Secretary?

And that's where my visit to Czechoslovakia in 1965 again proved lucky. It turned out that one of the people I met then, whom I've already mentioned, Zdenĕk Mlynář, was the closest friend of Mikhail Gorbachev when they studied together in the Moscow University Law Faculty from 1950-55. After the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, Mlynář resigned from his political offices and then later he was expelled from the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia as a "revisionist." After 1977, when he'd become one of the founder signatories of an oppositional document, Charter 77, along with Václav Havel and others, he was pressurized to go abroad as an alternative to jail. So he went to Vienna and lived there until his death in 1997. I was able to get an invitation for him to come to Oxford for a month in June 1979, and one day I asked him if he knew anybody in the current Soviet leadership and he replied, "Only Gorbachev". I said "Well, I'm especially interested in Gorbachev. He's so much younger than the others." And I asked Mlynář, "Would you say he's got an open mind?". Mlynář answered, "Yes, he's open minded, intelligent, and anti-Stalinist." Well, those were three very interesting attributes for a member of Brezhnev's top leadership team. I don't think any other member of the team had all three of those characteristics, and in particular, the open mind. So, from that time onwards, I paid special attention to Gorbachev.

Mlynář himself didn't publicize this friendship until Gorbachev had become General Secretary in 1985, because quite clearly, to be associated with a Czech revisionist, who had been expelled from the Party, would not have done Gorbachev any good at all in the Soviet Union. Likewise, I didn't quote Mlynář, and when I was consulted, as I was three times by Margaret Thatcher when she was Prime Minister, I made use of the knowledge I gained, but I didn't mention Mlynář even to her.

Natalie: I can see how that relationship would be very important to kind of keep discreet in such a closed system. Speaking of Mlynář and his life after 1968, you were in Prague for the period of the Prague Spring?

Archie Brown: I spent the 1967-68 academic year in Moscow University, so I was in the Soviet Union (mainly Moscow, but with a bit of time also in Leningrad) during most of the Prague Spring. I went to Czechoslovakia in October 1968, about six weeks after the Soviet invasion. There had been tremendous passive resistance to the military intervention, and the Soviet leadership had to make some temporary concessions. Dubček, the moderately reformist party leader, was reinstated for a limited period, but by the spring of 1969, all the reformers had been removed. But people, of course, still spoke very freely in the autumn of 1968 (and in private in subsequent years also).

Natalie: So, did you also have a perception from the Russian side about the Prague Spring events? What was going on in Moscow at that time in relation to those events?

Archie Brown: It made a huge impact in the Soviet Union. Among the people I met, many were quite excited by what was happening in Czechoslovakia. They liked the greater freedom they saw there, they liked the political reforms, and hoped that this might lead to something similar in the Soviet Union. That was true of some reformist members of the Communist Party (as I learned later) and of many non-Party intellectuals whom I met at the time. But at the top of the Party, there were deep worries about what was happening in Czechoslovakia and the KGB people were very agitated.

The atmosphere was quite tense because events in Czechoslovakia had alarmed the authorities so much. Even some foreign Communist newspapers stopped coming to Moscow University. Usually, at the kiosks there, you could buy the Morning Star (the newspaper of British Communist Party) or L'Unita published by the much more important Italian party (PCI), but those papers often failed to appear at the university kiosks because they were reporting things from Czechoslovakia which the Soviet authorities didn't want their own students to read. What you could read in Pravda and other Soviet papers about what was happening in Czechoslovakia was a very skewed, very unreliable account of what was really going on in that country. How worried the Soviet leadership were about the way things were going was later manifested when they sent some 500,000 troops put a stop to the Prague Spring in August 1968.

Natalie: Was the invasion heavily reported in the Soviet Union or was it also not mentioned?

Archie Brown: I left Moscow at the beginning of July that year. Of course, I continued back in Britain to read Soviet newspapers. There were articles about the attempted “counter-revolution” in Czechoslovakia which had led healthy forces within the Czechoslovak Communist Party to request “fraternal aid” from the Soviet Union and other Warsaw Pact allies. I don’t recall people in Moscow in May or June 1968 speaking about a likely invasion. For my part, though I theoretically didn't rule it out, it still came as a shock when it happened.

Natalie: You've written quite a bit about Gorbachev and perestroika, and I was wondering what it was about him in particular and that time period in Soviet history that captures your attention?

Archie Brown: I was well aware that it was very much a top-down system, so whoever was General Secretary could change the balance of influence within the system through having a greater say over appointments and policy innovation than anyone else. First, the General Secretary could appoint his own advisors. Second, bringing people into the Politburo was more of a process of collective co-option, but the General Secretary had a larger influence in that choice than anyone else.

So, my starting point was that Gorbachev was an intelligent man with an open mind, and that if he became General Secretary, interesting things could happen. I thought it was likely there would be reform in the Soviet Union under Gorbachev and that he was the best person to become Soviet leader both from the point of view of Soviet citizens and the outside world. How far and how fast he could go, that was another question, and he himself would not be able to answer it in 1985. His own views continued to evolve, and within a few years, he was under tremendous cross-pressures. It was an incredibly difficult task that only got harder as each year went by. By 1988, I would say the system was becoming different in kind, and in 1989, it was not really a Communist system anymore. The system had been pluralized, so it was certainly very far from totalitarian and was moving away from authoritarianism. There were contested elections, with party members competing against one another on quite different policy platforms for the new legislature - a legislature with real power. Marxism-Leninism was being either radically revised or completely abandoned by many party intellectuals, though conservative Communists clung to it. But it now had to compete with other ideas and ideologies for influence.

Natalie: Do you think one could draw parallels to Russia today, in comparison with that political structure that you just described?

Archie Brown: In some ways I think it was easier to analyze the strongly institutionalized Soviet system than contemporary Russia. There were rules of the Soviet game - rules of the game it took me some time to understand, and which were, of course, changing in the last years of perestroika. But we knew which institutions wielded greatest power, where power lay within them, what departments of the Central Committee did, how the nomenklatura worked, how significant the aides to the General Secretary were, and so on. It was possible to see who was on the way up, who was on the way down. You could see how well politicians in the top leadership team were progressing as they brought their own people into positions of power. That was especially clear in Brezhnev's time. You'd see Brezhnev gradually consolidating his power as more and more people who had worked with him in Moldova, Ukraine or Kazakhstan acquired leadership positions. There were rules of the game and norms of the system.

Of course, patron-client relations in Russia did not disappear along with the Soviet Union and, in widely varying degrees they exist in any political system. I don't these days study contemporary Russian politics. That’s quite a relief, for in some ways it is now more opaque. The Soviet Union was obscure to many people, but if you studied it carefully for many years, you could work out the way things happened. Nevertheless, one thing I would say by way of comparison is that it is wrong to regard contemporary Russia as just like pre-perestroika Soviet Union. Russia today is still freer than the pre-perestroika Soviet system was. Just look at the possibilities people have to get knowledge of the outside world, the possibilities of travel, and look at the kind of books, including some critical of the powers-that-be, that are published. I know that most newspapers are conformist (TV even more so) but there are still a few which are managing to retain a tenuous degree of independence. And, in sharp contrast with the Soviet era, the internet is now a hugely important source of information. Russia has become in many respects more authoritarian than it was in the later perestroika years or early post-Soviet Russia, but it's still much freer than the Brezhnev era.

Natalie: It seems you had an indirect influence on shaping political discourse, particularly during the late Soviet period in the 1980s. You mentioned your conversations with Margaret Thatcher, for example. In your experience, does advice from academic specialists ever make much impact on political leaders?

Archie Brown: I think a group of academics did have some influence on British political leaders. Margaret Thatcher participated in party political seminars, as distinct from government seminars, with people who were likeminded ideologically. But the three meetings in which I took part were not of that type. Two of them were well-organized government seminars at Chequers, the Prime Minister’s country residence. The other was a much more informal consultation at 10 Downing Street the evening before Mikhail Gorbachev arrived in Britain for the first time in December 1984. The most consequential of the meetings was held on 8th September 1983 at Chequers. Its preparation involved co-operation as well as tension between the Prime Minister and the Foreign Office. Eight academics were invited on the strength of our complementary areas of expertise, not on the basis of our politics. We sat on one side of the table with eight senior British government ministers and officials on the other side. They included the Foreign Secretary Geoffrey Howe and the Secretary of State for Defence Michael Heseltine, with Margaret Thatcher presiding and asking by far the most questions. I was there to talk about the Soviet political system, and I was the first speaker. I suppose the hardest thing to get across was that the Soviet system had a bit more flexibility in it than probably the Prime Minister assumed, and that there was a possibility of change from within.

We'd all written papers in advance, which the Prime Minister had read and annotated. In my paper I'd said that the change could come from within the ruling party as well as from outside. As you would expect from what I said to you earlier, I cited Czechoslovakia and the Prague Spring as a case in point, and that was underlined by Margaret Thatcher in her annotation of the text. Obviously, we had no access at the time either to her comments on our papers or to the much longer submissions from the Foreign Office and the Ministry of Defence, but years later I used the Freedom of Information Act to get all the papers in the run-up to and aftermath of that seminar declassified. I'd also mentioned Gorbachev in my paper as a likely future General Secretary and one who was reform-minded, and then I said a bit more about him in my oral presentation.

This seminar began at 9 a.m. and lasted for about six hours, if you count the lunchtime discussion - quite a long time in the day of a Prime Minister. We saw our role as getting these senior members of the British government to understand better what was happening in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe and how the systems worked, rather than to be giving policy advice. But at the end of the lunch, to our surprise, the Prime Minister asked us what our policy advice would be. We pretty much all agreed that the more contact the better, at all levels from general secretaries to dissidents, and we said so. I think that was good advice and, as we now know from declassified policy papers, it was in line with what the Foreign Office was saying as well. But Margaret Thatcher had a deep distrust of the British Foreign Office, and her relations over the years were to become increasingly uneasy with the Foreign Secretary, Geoffrey Howe. And so the fact that the academics at Chequers, whom the Prime Minister had the last word in choosing, gave advice similar to that of the Foreign Office strengthened their position. So, even if we didn't have an entirely independent influence, our support for the Foreign Office view mattered.

In fact, what several of us said was a bit bolder than the Foreign Office’s speculation. For example, their long paper prepared for the seminar (which, of course, we outsiders didn’t see back then) made no mention of Gorbachev. Naturally, there were people in the Foreign Office who were well aware that Gorbachev was the youngest member of the Politburo, that he had been to Moscow University, and so forth, but they didn't know anything about his values, his beliefs, his mindset. I, at least, knew a little about them, mainly as a result of my conversations with Mlynář.

The Chequers meeting was more significant than we could have guessed at the time. The declassified Cabinet Office papers refer to a new policy arising from it, adding that there would be no public reference to this change to a policy of engagement with the Soviet Union and, more broadly, with Communist Europe. The Foreign Secretary in the next year visited every East European capital. Margaret Thatcher began with Hungary, and then the invitation to Gorbachev was sent in June 1984, by which time he was number two in the Soviet hierarchy to Chernenko. Gorbachev and Thatcher had a long, long discussion at Chequers in December 1984, three months before he became General Secretary. That was a very important meeting because he and Margaret Thatcher argued of course, but they also got on very well; there was mutual respect. And that gave Thatcher a flying start, for this was three months before Gorbachev became General Secretary and a whole year before President Reagan met him at the Geneva Summit in November 1985.

Natalie: I also learnt that Ronald Reagan read your 1986 Foreign Affairs. Do you think it could have had an impact on his thinking?

I wouldn't claim for a moment to have had the slightest influence on President Reagan, but it was interesting to discover, as I did as recently as last year, that he read and annotated that article I published in Foreign Affairs in 1986 called "Change in the Soviet Union," which was given to him as part of his preparation for the Reykjavik Summit. The people in the US administration who had been most supportive of Reagan’s inclination to engage with Soviet leaders (in the face of Defense Department hostility and CIA scepticism) were Secretary of State George Shultz and Reagan’s excellent Soviet and Russian specialist within the National Security Council, Jack Matlock (who had succeeded a sceptic about improving US-Soviet relations, Richard Pipes). And, as I argued in my recent book, The Human Factor, Margaret Thatcher was also very influential in encouraging Reagan to engage with the Soviet Union. Especially from the time she first met Gorbachev, she was very much in favour of that kind of dialogue.

Natalie: How did you even find out that he'd read your Foreign Affairs article?

Archie Brown: It was thanks to James Graham Wilson, the State Department historian, who reviewed my book in H-Diplo and referred to it. He knew Reagan had read and marked this article. I had done research in the Reagan Presidential Library archives in California and got a lot of material there, but I hadn't come across that. But I wrote to the very helpful archivist who had been my guide to the collections when I was there, and she promptly emailed me the article, complete with Reagan's annotations.

You mentioned in advance of our conversation that you had learned that Reagan read this article and would be interested to know what he marked, so I have the article here and I’ll mention a few examples. For instance, I'd written that, "No Soviet leader in his first year of office has presided over such sweeping changes in the composition of the highest party and state organs as Mikhail Gorbachev”. Reagan marked that. I had a quotation from Gorbachev that a “radical reform is necessary." Reagan underlined that. I wrote that Gorbachev was “sometimes described misleadingly in the West as a technocrat. In reality, he is a politician to his fingertips." Reagan underlined "politician to his fingertips." And then he marked with double lines in each margin the final sentence of my article which read, "Though the fate of Gorbachev’s policy innovation will be determined essentially within the Soviet Union itself, it requires something more from the West than the stock response." So, at least the article didn’t do any harm.

I was glad to find out that Reagan read it, because when I came to write The Human Factor, which focuses especially on Gorbachev, Reagan, and Thatcher, I’d met Mikhail Gorbachev from 1993 onwards quite a number of times (and taken part in conferences he chaired) and, of course, Margaret Thatcher. The one member of the trio with whom, it appeared, I'd not had even the most tenuous connection was Ronald Reagan, but it turned out that there had been, at any rate, this indirect point of contact.

Current issues: On populism, democracy and its importance, and China.

Natalie: I have a couple of questions about the current state of affairs, or more recent history as it were. I wanted to ask about Boris Johnson and Donald Trump, and rising populism that seems to be more universal across the West. As a comparative politics analyst and leadership analyst, I thought you might have interesting thoughts about that.

Archie Brown: Well, I have written a lot about leadership and, in recent years, much more about British Prime Ministers than Russian leaders except for writing about Gorbachev. There are some things in common between the American and British politicians you mention, even if I think that Johnson wouldn't go quite so far as Trump. It was quite incredible to many of us that a President of the United States should declare a US presidential election to be illegitimate. It really made American democracy seem quite fragile. President Biden spoke about the fragility of democracy after that, and he didn't need to look very hard to find examples. It was right there in Washington, DC, with the invasion of the Capitol building and Trump's role in that, and especially with his denying that he'd actually lost an election, which everybody with any respect for evidence knew he'd lost comprehensively. I doubt Johnson would go that far, but there are lots of alarming aspects of his leadership as well. For example, there's been a lot of favouritism and nepotism in the way in which people have been and are still being appointed to senior public offices, ones where professional qualifications are meant to count for more than ideological alignment, personal connection or party allegiance. So, I would say British politics also is going through a worrying phase.

Natalie: And do you have any thoughts about their populist rhetoric and how populism more broadly is being proposed as an alternative to democracy?

Archie Brown: Populist rhetoric clearly is a problem. In the British case, it was very much to the fore in the debate over Brexit. There were lots of wild promises made, and lots of things stated as facts which were far from the truth. To an extent, that vote was won on false pretences and some of the problems that were foreseen by those who opposed Brexit are now becoming very evident. But there were lots of underlying reasons why the vote went the way it did. There's been increasing inequality, there are many parts of the country which are relatively deprived, many groups which have been losing out. People look for scapegoats, and in Britain, the European Union was turned into a scapegoat for problems and losses, despite the fact it wasn't the EU that was responsible for, say, the decline of British manufacturing industry.

I think the answer to populism is to improve the quality of democracy within our countries. This also applies to Russia-West relations. Rather than demonize the other side, we need to make our own countries more attractive. If you look at the end of the Cold War, I disagree completely with the triumphalist view that it was Reagan's increased military expenditure which forced the Soviet Union to run up the white flag. That's manifestly untrue. The Soviet Union found it far easier to compete militarily with the West than it did in terms of the attractiveness of greater freedom and a higher standard of living. People in the Soviet Union could see that the market economy was doing better than a command economy and they became increasingly aware of the advantages of democracy over dictatorship. In that sense, dismantling Communist systems and ending the Cold War can be seen as a victory for Western ideas, if you like, over Soviet Marxism-Leninism. But it wasn't a victory for the West in the triumphalist sense, which gives most of the credit to the Reagan Administration.

Mikhail Gorbachev was far more important for the change than Reagan who, after all, coincided with four Soviet leaders: Brezhnev in his last two years, Andropov, Chernenko, and Gorbachev. But nothing changed for the better in East-West relations, nothing changed in a more liberal or democratic direction in internal Soviet policy until Gorbachev became leader.

The general point applies now. If the United States and Britain could attend to their own problems, if there were more and better democracy in our two countries, that would count for more internationally than condemnation of Russia. There needs to be an end to gerrymandering and voter suppression, both of which damage and diminish American democracy. Unfortunately, our current British government seems to be going in that wrong American direction, for it is proposing to tamper with the independence of the UK Electoral Commission. (Needless to say, both US and UK elections remain vastly freer and fairer than contemporary Russian elections which are now far less genuinely competitive than was the March 1989 election for the Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR, almost three years before the end of the Soviet Union.) It would also help, internationally as well as domestically, if there were real levelling up, less extreme inequality, in the United States and Britain. Then, once again, these and other democracies would become more attractive, not least to people living in more authoritarian states. And I think that is a better approach than demonizing other countries. Better to start with your own problems and attend to them.

Natalie: Now, what are your thoughts on the current state of relations between Russia and the U.S. - you addressed this briefly, when you mentioned that we should not demonize one another, but I was wondering if you think there are specific areas that we can cooperate in? If you will "guardrails" on the relationship, be that START and other nuclear agreements that we have with them, counterterrorism, and other areas that we can discuss with Russia.

Archie Brown: In general, I think, one should engage. In the case of Russia and the United States, clearly there are several areas where dialogue is terribly important. Preventing nuclear arms proliferation is obviously one; keeping the nuclear treaties that exist and revitalizing those that have been lost. Dialogue on the whole issue of the spread of weapons of mass destruction is obviously important. Preventing man-made climate change is something that is or should be a common, and urgent, interest. There are other areas, such as cultural contacts, in which you can cooperate.

But I have to emphasize that it's more difficult to recreate trust that's been lost than it was to build up trust in the way in which it was gradually achieved between 1985 and 1991. In particular, from 1987 to 1991 (apart from a lapse, and loss of momentum, in the first half-year of the Bush administration) there was a relationship of growing trust between American and Soviet leaders. In the last years of the Soviet Union there was a relationship of trust also between Moscow and Western European capitals. That has been lost, too. And the fault is not, by any means, all on the Russian side; far from it.

George Kennan predicted that NATO expansion would lead to a new Cold War and in many respects the Russian eventual response has been along the lines that Kennan predicted. From the Russian perspective, NATO is still a Cold War frontier, and it's now closer to Russia. On the other hand, in countries that were forcibly brought into the Communist camp by the Soviet Union, people don't make an easy distinction between the Soviet system and Russians. They felt that they wanted to be members of NATO and have protection against Russia. My own view is that this has not increased their security. Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, what threat could they have been to Russia, if they were not members of NATO? Very small countries couldn't have been any threat. As members of NATO, they are a potential threat.

So, I think there was a tremendous lack of political imagination just after the end of the Cold War. There should have been pan-European security arrangements, to some extent building on the experience of the OSCE which embraced Russia. Certainly, it was important to embrace also the United States, but there wasn't much political imagination around in the USA or in West European capitals. We more or less sleepwalked into something which may or may not be called a "new Cold War." Such an excellent scholar as Robert Legvold has called it a new Cold War. There are, though, pretty important differences between the current situation – which certainly has got Cold War elements – and what I call the real Cold War. The real Cold War meant not only political, economic, and military competition, it was also competition between two universalist, proselytizing ideologies, with each claiming a monopoly of insight. I don't think either side has got such a universalist, proselytizing ideology now, or believes that it's got a recipe for the whole of the rest of the world.

Natalie: My other question is actually about China. I understand that you had the opportunity to visit China during the Cold War, and I was wondering, from a historical perspective, how you would compare the Soviet Union and Communist China? Are there lessons from the Cold War that are going to be applicable in the future of U.S.-China competition but more broadly Western-China competition?

Archie Brown: China has become more authoritarian, more autocratic in recent years. But again, China today is very different from the China of Mao Zedong. It is much more open to the world. There are a great number of Chinese people who are familiar with the outside world. Also, China now has a market economy, albeit with a substantial state sector, and is very important for the economies of many different countries because of its foreign direct investment as well as the number of multinational companies that do their manufacturing in China. So, of course I think there should be dialogue with China. The fact that Western countries continue to defend democratic values doesn't mean that we can't try to improve relations with such an important country as China. The idea that the United States somehow has to defend for all eternity its position as the world's most important power doesn't make much sense. Over time, which country is the most powerful in the world, or has the most vibrant economy, varies. Believe it or not, it used to be Britain, but that was a while ago. I think that it should not be an obsession of American academics or politicians. It's much more important that people should find ways of living peacefully on the same planet.

Natalie: In relation to that point, I was wondering how can the United States compete with China? As you mentioned before, the U.S. competed with the Soviet Union in this sense of great, universalist ideology and I was wondering what your thoughts were on how the West can compete with China and if you think there is an opening for either side to prevail?

Archie Brown: I don't see much of a universalist ideology from China, even though it is still a Communist state in the political sense, with the monopoly on power of the Communist Party and so-called democratic centralism within the party. But it is no longer a Communist state in the economic sense. There is the sheer diversity of the economy, with a strong consumer goods sector, and a lot of devolved economic power which is part and parcel of marketization. Perhaps the only universal recipe coming from China is the idea of combining authoritarianism with a reasonably successful economy. Obviously, neither Chinese nationalism nor Russian nationalism is going to have an appeal outside China and Russia and some segments of their diasporas.

It's quite different from the international Communist movement of the Soviet period. In spite of the Sino-Soviet split, this was a huge and significant movement. The leaderships of Communist Parties from all over the world went to Moscow and, for the most part, accepted the authority of Soviet mentors. This meant that in every country there were people, if it had come to a war in which the world was not destroyed, who would take power and accept instructions from Moscow because they actually believed in this universalist ideology of Marxism-Leninism and the Soviet Union’s leading role in the international movement. There would be others joining as opportunists, but together they would use Communism as a path to power. That scenario contrasts with the lack of appeal in other countries of contemporary China’s political doctrine, though China does, of course, have economic levers it can use.

China is very insistent that Taiwan ultimately belongs to China, that Hong Kong does, and it is not sticking to its agreement on Hong Kong - one country, two systems. But Taiwan has had de facto independence, and probably they would be unwise to pursue de jure independence because de facto independence is worth quite a lot. If Taiwan can maintain its political autonomy and continue to combine economic success with democracy, then it may have some influence on mainland China. But that is doubtless something that worries the leadership in Beijing. It's a complicated question. But I don't think it's as hard to live with China today as it was with Stalin's Soviet Union. So, I don't really see why there should not be dialogue with China and agreement in some areas. Overwhelmingly important climate change affects everybody, and China's got a tremendous ecological problem. They've started to recognize it because, as you know, Beijing this century has been just choking with pollution.

Natalie: Yes, absolutely. That is, I think, certainly one area we can all hopefully cooperate on in the future.

Message to future generations

Natalie: What advice you would give to a young professional in the field of Russian and Eurasian Studies? And I ask this question in the spirit of true openness, so it doesn't necessarily need to be professional advice, it can also be life advice.

Archie Brown: I've been retired from university teaching for quite a while, but I've met some of the University Consortium students from a number of countries: America, Britain, Russia. I've been very impressed, so I don't think they need any advice from me. But for what it's worth, I would say I think it's important to have a comparative perspective. I don't think one should be a narrow area specialist. Having said that, some of the narrowest area specialists in the world are those working on American politics. There are people who do research only on American politics and they then become quite disparaging of those they call "area specialists." But these area specialists may study several countries in Europe, or Russia and Eurasia, whereas if you spend all your time studying voting behaviour in Michigan you would not be an area specialist, but, curiously enough, a really serious political scientist. There is a great deal to be said for knowing about more than one country. Studying British as well as Communist politics made me realize there are some features of politics that apply in democracies and in authoritarian regimes. And, as I've already emphasized, going to Czechoslovakia helped me understand the variety of sources of change in Communist systems and what might happen in the Soviet Union. It opened my mind to possibilities there that weren't there before. More generally, you can’t adequately understand your own country unless you have serious knowledge of at least one, and preferably more than one, other country. What you think is uniquely good about your own may, in fact, be done better elsewhere, and what you think has universal applicability may be more culturally specific than you imagine.

Also, ideally, a graduate student, in the social sciences most obviously, has some knowledge of statistical methods, and if studying non-English speaking countries, a foreign language. But of course, in graduate schools, these things are often seen as alternatives. Either you go down a statistical and mathematical route or you go down a linguistic route. In an ideal world, you'd have some knowledge of both, but the way graduate schools are organized, often that's not easy to achieve.

I suppose one last piece of practical advice would be not to postpone writing for too long. You can carry on researching forever, and there comes a point when you've got to write. And often it's in the course of writing that your own ideas get clarified. There have been times when I was not entirely sure what I thought about a particular subject until I started writing, and then, in the course of working through the argument, it became clearer.

Natalie: That's particularly good advice for those of us just embarking on our master's theses. Thank you very much for that, and thank you very much for your time, Professor Brown, I really appreciate it.